Doomed to succeed

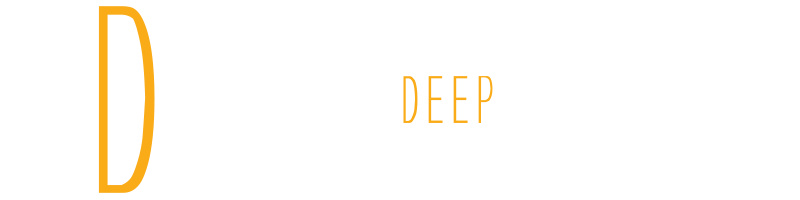

Inclining test

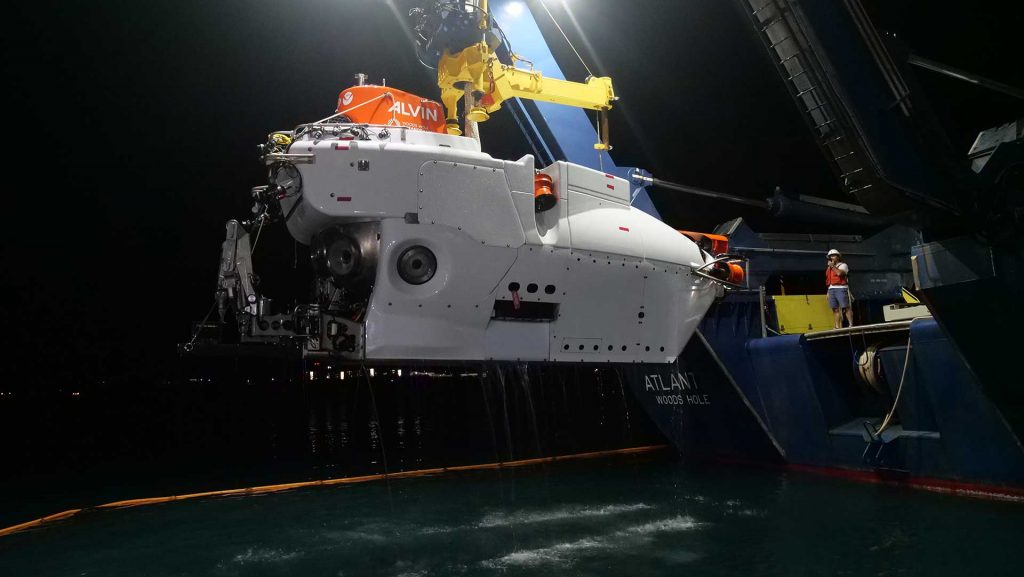

Yesterday (Monday), Alvin successfully completed its Navy-mandated inclining test that is used to verify a ship's stability. The test involved moving known weights between the ends of a bar bolted to the back on the sub and measuring the resulting roll angle, both submerged and at the surface. It made for a long day, but conditions were ideal. Nevertheless, it was dark when Alvin came back on deck and released three very tired divers to applause from everyone. It's a major step in the sea trials process, and one that has allowed us to proceed today to a shallow harbor dive. If all goes well, we'll be leaving Bermuda tomorrow for the first open-ocean dives northeast of the island and eventually to its deep dive on the edge of the Puerto Rico Trench.

Doomed to succeed

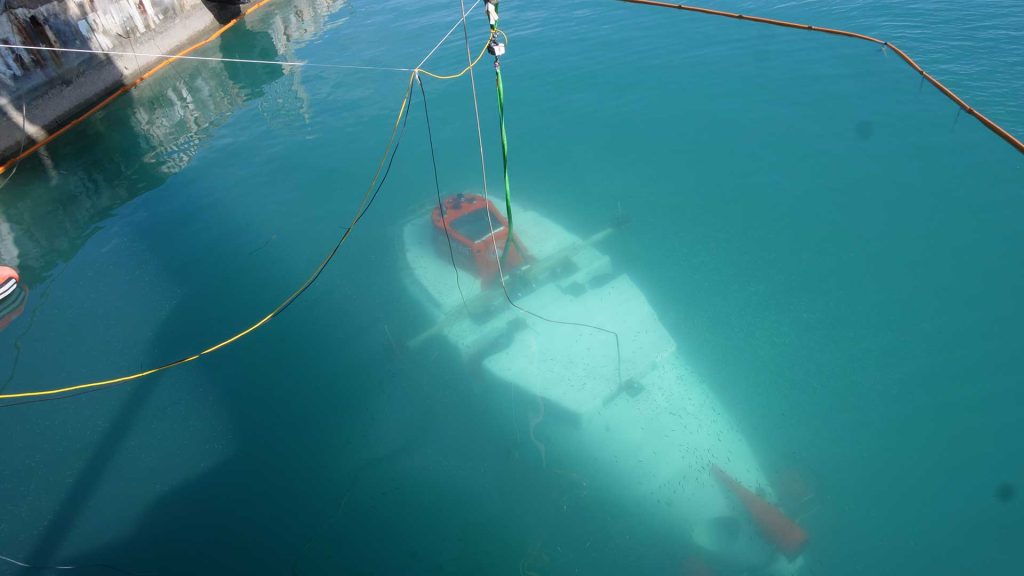

Alvin hasn't competed a deep dive since it's overhaul, but in a computer in a corner of one of the labs on Atlantis, it dives all the time.

WHOI software engineer Stefano Suman is on board to ensure that the sub's programming is ready to take scientists in Alvin deeper than they've gone before by using a technique he and other designers working on robotic vehicles like the autonomous underwater vehicle (AUV) Sentry and the hybrid remotely operated vehicle (HROV) Nereid Under Ice have used for years. He's running simulations of dives to identify bugs and make the complex software operating throughout the sub more efficient and more resilient during a dive.

"A simulation can be 90-95% accurate," said Suman. "With a couple of actual dives, we can get that to maybe 98% accuracy. We say simulations are doomed to succeed."

The computer in the Hydro Lab near Alvin's hangar contains computer code that simulates all of the sub's sensors and other systems. With data from a previous dive feeding into it from another computer, Suman can watch his virtual Alvin respond to conditions it might encounter. When he finds problems, he fixes them without having to abort the dive and bring the actual sub to the surface, thereby losing valuable time at sea.

The only problem is, he sometimes has to work late into the night, as he did recently. That's because for Suman to do his work, he needs a period of time with the sub powered up. But the mechanical and electrical engineers who are troubleshooting their systems at the same time, occasionally have to power down the sub in order to work.

So, after the sub came out of the water from its first official, post-overhaul dive on Thursday, Suman went to bed, got up at 1:00 a.m., and used the off-hours to work uninterrupted through the night on the sub's navigation system. Yesterday, during the inclining test, he rode along for the entire dive to compare his simulation to the sub's actual responses.

Unfortunately, just as he's always pinched for time in the competing demands of mechanical and electrical engineers, Suman is pinched for time in another way, as well. He won't be able to see all of Alvin's open-ocean dives because he's committed to another expedition in the Pacific with NDSF Chief Scientist Anna Michel leaving from San Diego in a week with Sentry and the remotely operated vehicle (ROV) Jason. So, after Alvin's first few dives near Bermuda, he'll have to take a small boat back to shore, then head to the West Coast for his next assignment bridging the real and virtual worlds.